Conversations about racial equity often bring discomfort. Many educators, leaders, and community members struggle with defensiveness or silence when issues of racism and privilege are raised. These reactions are not random—they are linked to shame. The compass of shame is a framework that explains how people typically respond when they feel shame. By understanding these responses, schools and communities can begin to address barriers to equity and create healthier spaces for dialogue.

Why Shame Matters in Equity Work

Shame is a powerful emotion that can block progress. In discussions about race, it appears when individuals feel criticized or exposed. Rather than leading to reflection, shame often sparks resistance. Some people deny racism, some deflect responsibility, while others retreat completely.

Even though shame is uncomfortable, it is not inherently negative. It can push people to reconsider their beliefs and behaviors. The challenge lies in how we handle it. When schools and communities use restorative practices, shame can become a doorway to growth instead of an obstacle. The compass of shame helps explain these dynamics in practical terms.

Understanding the Compass of Shame

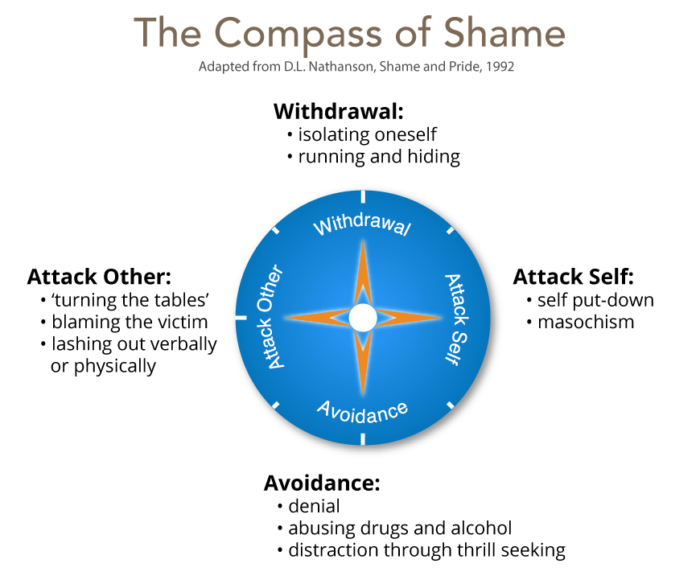

The compass of shame shows four common reactions to shame: attacking others, attacking self, avoidance, and withdrawal. Each response shows up in different ways during conversations about racism.

-

Attacking Others: This response shifts blame onto someone else. People may argue that raising issues of racism is unfair or even accuse others of “reverse racism.” This behavior attempts to silence the original concern instead of addressing it.

-

Attacking Self: In this response, guilt becomes self-criticism. Individuals admit racism exists but turn the focus inward, blaming themselves excessively. This often leads to short-lived attempts to “fix” things, without addressing systemic issues.

-

Avoidance: Avoidance hides the problem. People claim to be “color-blind” or insist their community does not have racial problems. By denying reality, they avoid difficult conversations.

-

Withdrawal: Withdrawal means stepping away altogether. People acknowledge inequality but remove themselves from the discussion. This might look like changing the subject or leaving the space emotionally.

Recognizing these responses helps us see why progress can stall. On platforms like akoben llc, restorative strategies are taught to move people away from these defensive patterns and toward honest engagement.

Shame and Leadership in Schools

Schools reflect broader social issues, and shame is often visible when racial disparities are addressed. Discipline data, achievement gaps, and bias in curriculum all reveal inequities. When these truths come up, the compass of shame explains the resistance educators may show. Some may attack the idea of systemic bias, others may express guilt, and many may disengage.

Leaders play a crucial role in shifting this culture. They must be willing to model openness, even when conversations are difficult. By creating spaces where shame is acknowledged but not avoided, leaders encourage growth and resilience. Restorative methods help educators transform reactions into reflection and accountability.

Equity leadership is not about perfection but persistence. It requires courage to stay present in conversations that trigger discomfort. Dr Malik Muhammad has demonstrated through his work that confronting shame directly can build stronger communities. His approach shows that with the right support, leaders can turn resistance into transformation.

The Human Side of Transformation

Racial equity work is not only about data or policy—it is also about people. Shame is deeply personal and influences relationships. How individuals respond affects whether communities grow closer or further apart. Recognizing this human side is essential for meaningful change.

Many advocates have shown how to move through shame with compassion. Their work highlights the importance of patience, accountability, and empathy. Iman Shabazz has emphasized that equity efforts must honor both personal and collective journeys. Her insights remind us that facing shame requires courage, but it also opens the door to healing and deeper connection.

From Shame to Growth

The compass of shame does more than identify patterns—it points the way to better responses. Once we know the typical reactions, we can choose differently. Instead of attacking or avoiding, people can practice listening. Instead of withdrawing, they can stay engaged with support from restorative practices.

Circles, open discussions, and reflective questions are tools that allow shame to be addressed without shutting down dialogue. When guided carefully, these methods create environments where people learn from mistakes and build stronger commitments to equity. The process is not easy, but it transforms shame into motivation for change.

Conclusion

The compass of shame provides a clear lens for understanding resistance in conversations about race and equity. By naming these responses—attack, avoidance, self-blame, and withdrawal—we gain insight into the emotional challenges that block progress. Schools and communities can then use restorative approaches to shift from shame to accountability.

The work of leaders and advocates, including Dr Malik Muhammad and Iman Shabazz, shows that transformation is possible when courage and compassion are present. By confronting shame directly, we move closer to equity and justice. Real change happens when we choose engagement over avoidance and healing over silence.